Why Slow Decisions Kill More Projects Than Bad Ones

Two of the biggest tech headlines this week were somewhat unexpected collabs: Apple and Gemini teaming up on a new Siri, and Eli Lilly and NVIDIA co-creating AI drug discovery lab. I’ll argue the through line here is that companies are recognizing the importance of data to advancement. Gemini has LLM prowess but Apple has years of Siri data. NVIDIA has the chips everyone wants but Eli Lilly has mountains of clinical testing data on successes and failures of past drugs. With technology plus data, you can innovate faster. But why?

Because innovation doesn’t happen in one giant leap. It’s thousands of decisions, stacked on top of one another. What to pursue? What’s the timeline? How much can you invest? When something goes wrong, do you pivot or smash through like the Kool-Aid man in a ‘90s commercial? Each of these decisions falls to a leader. While that leader is pondering, nothing moves forward. If the leader makes the wrong decision, things may fail to move forward.

I’m wrong a lot. You’re probably wrong a lot too. Being wrong is one of the most common things leaders do, often eclipsing the incidence of being right (though we’d probably never admit it). And you can survive being wrong fairly often and still have thriving tech (and other) initiatives, as long as you identify mistakes quickly and correct course decisively.

Still, if you could be right more often, that’s probably appealing. Being wrong is about as much fun as a colonoscopy, and it comes up a lot more often. Making better decisions would lead to less wasted time and less wasted credibility. It doesn’t take a scientist to recognize that, but we have credible data to back it up. McKinsey found that organizations that make high-quality big decisions quickly and execute them fast are more likely to report ≥20% financial returns from recent decisions.

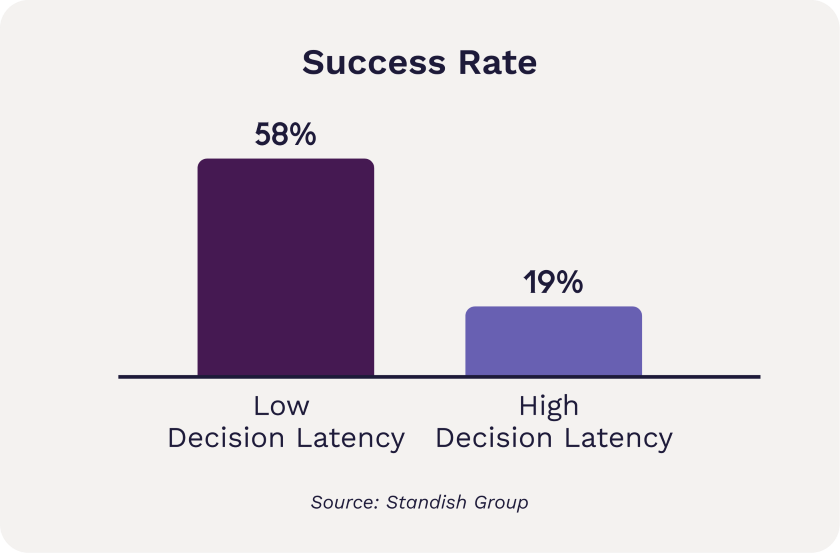

Notice that while being right gets a lot of attention, speed matters too: delayed decision-making is toxic to project success. Faster decisions mean a more efficient team who wastes less time waiting for you to figure out what to do. Even a fast wrong decision can be better than a slow wrong decision. It at least gets the team moved off of center so they can figure out it was a mistake and everyone can fix it and move on. The Standish Group’s CHAOS data of tens of thousands of projects lends empirical evidence to this idea, in its “Decision Latency Theory,” which concludes that the interval between a decision request and a decision is a primary driver of software project success or failure.

So what’s a slow decision vs. a fast decision? Standish found that projects with average decision latency under one hour have about a 58% success rate, while those with decision latency over five hours drop to an 18% success rate. In other words, a fast decision is one that you make in less time than it takes to get an Uber Eats order from your favorite ramen house during the dinner rush. Anything over that and not only are your noodles cold, but your project is probably suffering.

It’s not about clairvoyance

Like paying for priority to get your order sooner, any leader can get better at making faster, higher quality decisions—for a price. And the first step is to get out of your own head. It’s easy to buy into the mythos around leadership that effective leaders have a special brand of mental clarity that enables them to see the future like no one else.

That’s nonsense. The best leaders I know aren’t any more psychic than anyone else. What they are good at is:

Staying calm long enough to identify what they need to know to make a high-quality decision

Allocating the resources to get that information quickly

The identification part can trip even smart people up, because the pressure to make a decision can interfere with thinking clearly about what you don’t know. There’s a tendency to panic when we don’t know something and throw up our hands. If you can resist that urge, you can normally identify what would help you get to an answer. To put it in math terms, you’re often investigating your constraints: what are the bounds within which this decision operates?

Once you have identified what you need to know, you can set about acquiring that information. And this is where things often really fall apart. Often truly knowing would require a data exercise: sourcing, scrubbing, querying and analyzing. In most cases, that takes over an hour. Maybe even weeks or months. With the high cost of decision latency, that’s too long. So most leaders guess and operate on hunches or pre-existing biases. Fast, but not high quality.

In order to be set up to make high-quality decisions quickly, you have to anticipate the kinds of data that are most valuable to you, and start gathering it before you need it. For example, in our business, time tracking data is highly valuable. We work on a fixed bid basis most of the time, so our ability to make a sustainable profit depends on how well we can guess the time needed to complete a project. And the best indicator of that is past data for similar work. We can’t wait until it’s time to quote a project to ask people how long the last similar project took—there’s no way they’ll remember accurately. We have to make it a practice to gather the data consistently, as work happens, because we know we may need it later.

Most businesses have parallels. There are certain types of data that you can reasonably anticipate will influence future decisions. Laying the infrastructure to begin to gather that data is one of my top recommendations to be a better leader.

Don’t be put off if gathering the data seems difficult at first. We’ve built dozens of custom data gathering solutions, including the way we track time. While it takes a bit of doing to get it going, that investment continues to pay dividends year after year.

If your plans include AI, investing in that data is even more important. AI doesn't just help you analyze data faster—it can reveal patterns you wouldn’t notice and flag anomalies for further investigation. But AI is only as smart as the data you feed it. The companies making ROI-positive investments in AI right now are first investing in their data. That's why this week’s splashy partnerships make sense: Gemini's LLM is powerful, but it needs Apple's decade of Siri interactions to become genuinely useful. NVIDIA has the best chips, but it needs Eli Lilly’s stockpile of data to analyze past compounds that have worked—and those that haven’t. Your AI ambitions work the same way.

Don’t be afraid to find out if you were right or wrong

The flip side of gathering the data in advance is that you also want to reflect back on how you did after the decision was made. Were you correct? If not, can you see what you missed that caused the error? And often that means, you guessed it, more data.

One of my favorite parts of customer discovery is discussing how we’ll know if we nailed it. It’s useful to think about the specific metrics that will identify success (and also warning signs). For example, every time we build an onboarding flow, we also build some custom tracking with it. It took considerable effort to figure it out the first time—now we get to draw on that knowledge every time we do it. Because we have detailed data, we not only start with a strong base for each new onboarding flow, but we can continue to refine over time because we’ve thought through how to identify places where users are dropping off. We have the data we need to make decisions quickly.

One of the best parts of the process of thinking through metrics is the forced humility. It’s good for all of us: leaders, subject matter experts, operational team members—to acknowledge that we’re going to be wrong sometimes, and to put a process in place to catch it and correct it. It requires a willingness to confront our own shortcomings, but like that $2.99 priority delivery fee on Uber Eats, it’s a small price to pay for faster, better decisions.

If you’re looking to make better data-driven decisions in 2026, we have a product for that called Rover. If it’s intriguing, great—if not, I still hope the thinking here helps.