AI and Employee Portals: How to Be a Success Story

Simulated Reader Question:

Veronica Hawkeye* (Veri Hawkeye for short) asks:

I hear a lot of hype around AI but I also see that a lot of pilots are failing. We want to use it to help our employees but don’t want to fail. Failing is a bad look, and I don’t want to be the one explaining to the board why we lit money on fire. Are there valid AI investments right now for internal employee use?

Thanks for the question, Veronica. Yes, in fact internal employee portal uses of AI can be some of the best investments right now. To see why, first, let’s dive into what we mean by the popular storyline that a lot of AI pilots are failing.

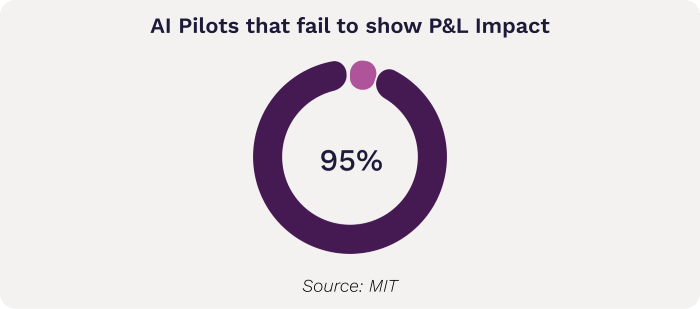

Some people might think this means the AI doesn’t work, but that’s actually not the prevailing issue. For example, MIT’s study of generative AI pilots defines success as delivering “measurable P&L value”, which only 5% of generative AI pilots in the study achieved. That’s astounding and notable, but it’s not the same as the tech itself not working. It’s actually a classic problem we see over and over again in internal tech projects. I’m going to be talking about AI tools, but this really isn’t any different than any other technology transformation initiative. You could replace 'AI' with any other enterprise tech initiative and these same dynamics apply.

In order to create that measurable value, let’s walk through what would have to happen:

The AI tool is successfully created in pilot. By success I mean that the technology works as expected.

AI tool is deployed in production to one or more business units.

AI tool achieves critical mass adoption.

The business units are able to reduce headcount, redirect people towards other revenue-increasing or expense-reducing activities, or the tool itself directly increases revenue or reduces cost.

Step 1 is not (generally) the problem. Companies are creating pilot tools that do what the technology is meant to do, for the most part.

Step 2 inspires some dropoff. The reason for this is that the bar to deploy to production is often a lot higher than the bar to create a pilot. Companies must spend more money, get compliance involved, train users, evaluate risk, secure the solution and perform iterations to achieve usable output. Edge cases are tested. Limitations in data are identified. Some of these hurdles are not quick or easy to solve, and if the company has not planned for this phase, the project may languish.

This is essentially a failure of the business case—the company did not have a plan for meeting security, compliance and risk challenges, or did not plan for the process to involve iteration.

Step 3 inspires even more dropoff, especially if the approval at Step 2 was rushed or testing was insufficient. Reasons for failure may be that there’s not a built-in iteration loop, so the error rate isn’t improving over time and users lose interest. Or, the process may simply not be tuned well enough to the users’ actual workflow.

This is essentially a failure of UX and testing.

Step 4 is the real kicker. Across all of the AI Readiness Assessments we’ve done, there are many instances of teams dreaming of AI to solve a problem or handle a task that’s personally annoying to them, but which may not take very much time. If it only takes 10 minutes per month and there’s no other increase to revenue or decrease to cost, it’ll take a long time for the investment in AI to pay off. Dreaming can be productive so I’m not suggesting companies stifle this ideation, but it bears another step to evaluate the cost and possible benefit.

This is also a failure of the business case, which might also be wrapped in a failure of UX and design.

What can you do to make your employee portal AI project successful?

If we look at the steps above, we have two major failure points: failures of the business case and failures of UX and testing.

Failures of the Business Case

When we look at failures of the business case, this often stems from early enthusiasm blotting out reality.

For example, teams may suggest a use for AI that would produce a meaningful savings if it could be fully automated, but because it’s a high stakes process, the tolerance for error is next to nil and it would still require human observation. That’s not always the kiss of death for an AI project (in fact there are ways to work with this productively that I’ll cover in a minute) but if this is not identified early, the company may produce a pilot that can’t be promoted to production because the business can’t tolerate the failure rate.

When we’re working with clients, we mitigate this upfront by steering the early conversations toward uses that have built-in guardrails: using AI to assist, but not replace, human discernment. For example, AI might flag orders that likely need a closer look, or suggest a likely answer based on information but allow the human agent to override.

Hype and enthusiasm might also cause users to overlook security or compliance concerns. How the underlying model is hosted, and how you interact with it, matters. For many business cases, accessing models like ChatGPT via their API may not be sufficiently secure or comply with industry regulations if you’re passing customer data. You need a solution that protects the data. There are a variety and that’s probably too far in the weeds for this post, but the most important thing is to plan for how to secure the data upfront, not as an afterthought. If the wrong model or platform has been used to produce the pilot, it may require a substantial rewrite to correct. To give you an idea, this is one of the first things we determine when working with our AI Readiness clients, so it’s set before a single line of code is written.

Finally, the business case may lack grounding in real metrics. Earlier, I brought up the example of automating a task that’s deeply annoying to a particular employee or group of employees, but objectively doesn’t take much time and therefore doesn’t make a great case for investing in fixing it. That’s largely true, and a lot of failed AI use cases fall into this category. That said, there are a few reasons where those deep splinters are worth digging out, such as:

Not only is it annoying, but avoidance is leading to extreme frustration and possibly even a slowdown in workflow. Some sources of frustration go beyond the actual time spent and can have an outsized impact on the team. For example, within our team, a repeated source of teeth grinding was the communication between dev and QA: Dev notifying QA when something’s ready to test or retest, QA notifying devs when something passes or there’s feedback on issues. Does that communication take long? No, it takes seconds. But people would forget to do it, and other people would get annoyed, and the overall consternation around it made automating worth it, even though the actual time spent probably didn’t look like it on paper.

It’s introducing errors. Some frustrating tasks can also create very costly errors. If it’s frustrating because it’s difficult or error-prone, or because it’s stressful due to the stakes being very high, automation makes sense. For example, we’ve automated a number of quoting processes for various clients. The main driver there isn’t time savings (though there is some), it’s consistency and reducing high-cost errors.

There’s a single point of failure. If the entire business unit’s success relies on knowledge that lives only in the mind of one key person, we have a single point of failure. You never know what could happen. People can unexpectedly need time off. The business could grow and one person might not be sufficient to keep it running. Planning for automation to reduce reliance on one person is a smart sustainability move for the business.

Even if you have one of these special circumstances, it’s still critical to work to quantify the risk to the business vs. the cost of developing the feature. There are many problems in business, not all of them need solving today.

Failures of UX/Testing

Failures of UX and Testing happen a bit further downstream. The business case made sense, but the execution didn’t support it, either at the design stage or the testing and iteration stage.

First, let’s look at failures in design. Most of these are around either failing to understand the way people do their jobs, or failing to account for the way AI does its job.

There’s absolutely no substitute for interviewing real employees about their real experience doing their day-to-day work. They know what they do, all the nuance it covers, and they also have a good idea of what matters to your customers. Tailoring the AI to fit the workflow means considering things like where does the tool live? What does it know already when the user initiates a prompt? Can it determine contextually based on where they initiated from (for example, knowing what ticket a user initiated a session from) or do they have to re-type all of that? Those kinds of design choices can mean the difference between something truly useful and something that people say “huh” and go back to what they were doing.

Just as importantly, these must contain a built-in mechanism to correct the AI, or adoption will eventually stall. People can get on board with training AI, but if they have to correct it forever without seeing signs of improvement, they will give up in favor of what they’ve always done. There are many ways this can be done. The user can explicitly correct the AI via a chat interface (leading to the now-familiar apologizing and pandering). The system can collect data on which recommendations were used and which were not. There could be a hybrid approach where the user flags records that don’t look right, and those are later fed to the model to train it further.

Regardless of method, accounting for making the AI smarter over time helps you ensure a successful outcome.

Stay on the right side of gloomy statistics

Your organization has its own unique blueprint, and your risks may lie more on the business case side or more on the UX side. The solution for both is the same: slow down, keep your eyes clear, and work the process. Everyone wants to be in the 5%, not the 95%. The good news is, the pie can grow for everyone. I’d love to see more and more companies adopt clear-eyed approaches to AI and start driving those aggregate numbers up. It benefits all of us.

If your organization wants help with the business case or the UX design and testing, both are included in People-Friendly Tech’s comprehensive AI development services. Drop me a line if you’re interested.

Notes

*Not a real person, this is an alter ego I made up to synthesize questions people ask us casually in conversation into something I can answer in a more universal way in the newsletter.