What the Mobile App Rush Taught Us About Betting on New Tech

The hype is starting to cool a bit on AI, and that allows the business world to see a bit more clearly, and recognize that yes, this was another hype cycle and yes, this too shall normalize. But we’ve seen this before. This is the second wild hype cycle directly impacting custom development that I’ve lived through in my almost 19 years of owning a tech business: the first being the app rush in the early 2010s. Let’s use that as a baseline to understand how these hype cycles play out long-term, and how businesses can best make decisions during this time.

The thing about hype cycles is that there’s both an overblown sense of FOMO around them, and also a kernel of something compelling. The hype doesn’t exist if there isn’t actually something useful in there, and yet the sudden gold rush mentality can make it feel like you’re missing out if you don’t sell all your belongings and grab a pickaxe to spend the next year wading barefoot in muddy water. And yet, while a few who heed the call will prosper dramatically, many will come back empty-handed.

The difference between SMB and Enterprise hype investment styles

In the app rush 15 years ago, what we saw was a wave of interest by businesses of all sizes to investigate mobile apps. But while businesses of all sizes had interest, the behavior was different based on size. Many SMBs commissioned proposals, and after seeing the cost, a large portion didn’t move forward. Many larger entities, for whom the cost was a small fraction of their budget, forged ahead.

The use cases pursued were also different. Contrary to what one might expect, the SMBs who did move forward were often placing riskier bets than their enterprise counterparts who often pursued efficiency bets. By riskier bets, I’m not necessarily referring to the size of the investment, but the nature of it. SMBs tended to pursue use cases that were an entirely new venture for the business: a SaaS product, a brand-new line of business, or even creation of something the market hasn’t seen before. I’ll refer to these as growth investments. They don’t service existing business better; they create an entirely new category for the business. These are riskier because they require significant new adoption to achieve ROI. Why were small businesses, who generally have more limited reserves, willing to place riskier bets?

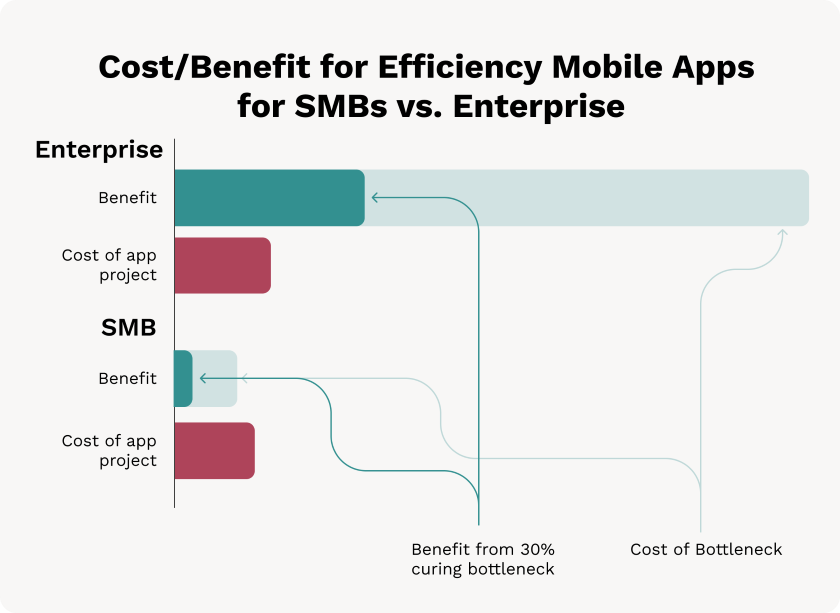

A combination of opportunity cost, personality, and hype. Opportunity cost is the easiest to understand, so we’ll start there. Earlier I mentioned that larger organizations were largely investing in apps as efficiency bets. What I mean is that they found an inefficient process somewhere in their operations, determined that an app could help solve it, and deployed it. While some of these bets have secondary ROI potential to increase revenues over time, the primary driver was reducing bottlenecks. This is comparatively more accurate to forecast: find the bottleneck, measure the cost of it, multiply by a factor for how much of the bottleneck you think you can cure with an app. A $10 million bottleneck that you can improve by 30% is 3 million in savings per year—more than enough to justify an app investment. As long as the app is well-designed and executed so that it truly solves the bottleneck, the savings is likely to be captured. And this is borne out by what we saw. Most large organizations’ bets were successful at returning positive ROI, though they may have accelerated an existing trajectory more than they changed the direction of the organization.

For SMBs, however, the factors are the same, but the pie is smaller. A 50K bottleneck that you can make 30% better is only a 15K savings per year. While the cost is also generally a little less for an SMB, who tends to have lower expectations for handling edge cases, the benefit is often not enough to justify creation of an entirely new app, nor the cost to maintain it. This means that efficiency bets just weren’t worth it for a lot of SMBs. Their opportunity cost to not pursue an efficiency bet and take a big swing instead was 0.

There’s also a personality difference. SMBs are often led by founders with a healthy appetite for risk. Larger organizations tend to make decisions by group, and that necessarily means that unless there’s a very risk-tolerant culture, they generally make more risk-averse decisions. SMBs have fewer people involved in decisions, and those people often have a higher tolerance for risk. In most industries, the odds are stacked against a new business. Those who decide to open one anyway must intrinsically believe that they can succeed despite those odds.

A leader at a large organization might think “If I take this big swing and miss, it may succeed and change our trajectory, but it also may fail, which would bring a good chance that I’d get fired. However, if I make the efficiency bet, it’s more likely to succeed and less visible if it fails.”

A leader/owner at an SMB might think “It’s my money and I think this can work—I’m going to take the risk because it’s worth it to me to know that I tried. If it fails, I can live with that, but I think it has a good chance to succeed.” And that’s enough, they have the power to make that decision—and live with the results, good or bad.

The allure of passive income

The final factor is a separate, specific hype cycle that mostly impacts SMBs: the passive income movement. Passive income is the dream for most entrepreneurs, though I personally think it’s a misnomer (I’ve known many successful entrepreneurs with ‘passive’ income and they sure seemed active in their businesses to me). That said, recurring revenue is an understandably sexy draw for SMBs and it can certainly pay off.

Companies like 37 Signals come to mind—a company that was originally a web consulting firm that achieved revenue growth and stability through their SaaS product, Basecamp. So it can work, and the fact that it can work and entrepreneurs have to have a little extra dose of belief in their own agency means that it’s extra attractive to them.

The attractiveness of projects that would yield passive income, combined with the risk tolerance of entrepreneurs and the relatively low opportunity cost means that many SMBs pursued apps that were riskier, but with more potential upside. So how did that work out?

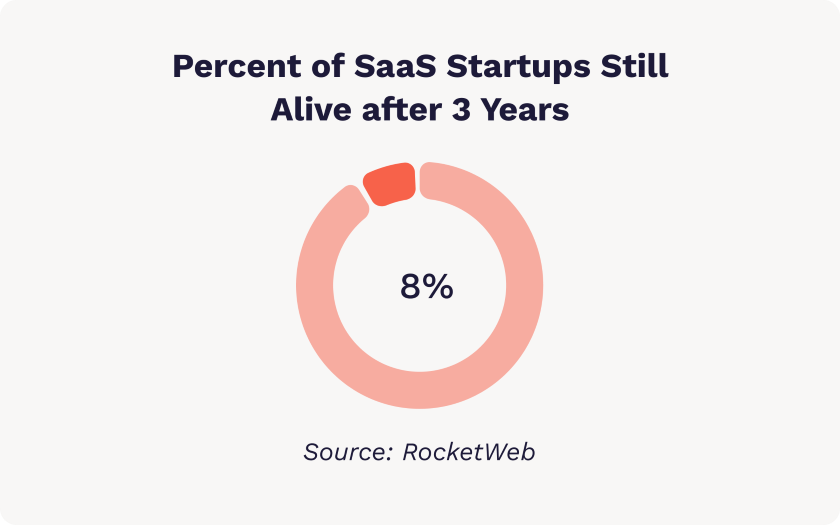

Industry-wide statistics say that about 92% of SaaS startups fail within three years, or in other words about 8% of SaaS products (the best approximation I could find for growth projects) are still around after three years.

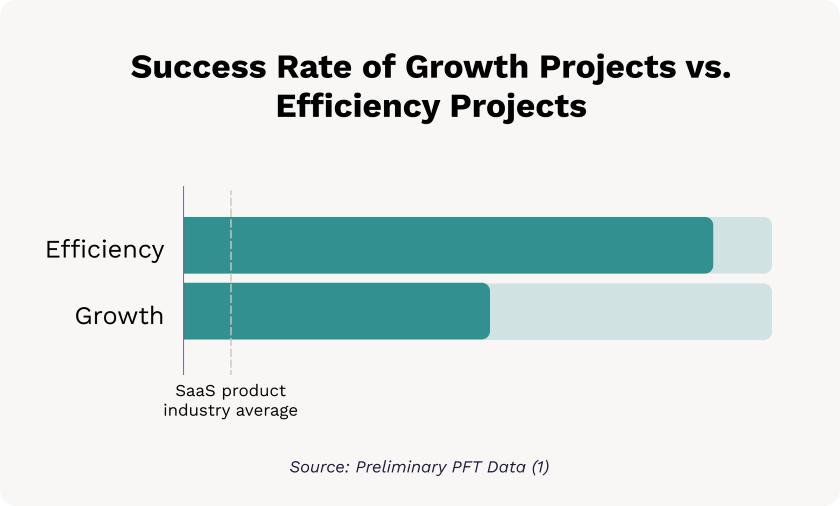

I’ll provide more info on this in another post soon as we’re working on a formal report, but we compiled our data for 10+ years of projects to examine trends (1). Don’t hold me to this as we’re still doing some data cleaning, but preliminary results show that we do quite a bit better than the industry average for growth apps of 8%, but we still see a difference of 52% success rate for growth projects, as compared with 94% success rate for efficiency projects using the same standards.

What does the original app rush tell us about mobile app investment today?

The data is clear: mobile apps are a strong investment for some businesses, but not all or even most.

If you’re considering an investment, ask yourself which category this investment falls into:

Is it an efficiency app, allowing you to serve existing markets better?

Or is it a growth app, requiring you to expand into new markets or build an additional customer base?

Efficiency apps have a much better success rate. There’s no such thing as a guaranteed success, but they’re close to it as long as you do your homework on the business case (and we can help with that).

If you are interested in a growth app, that can be successful, but the best tech doesn’t matter unless you can make inroads in that new market. That usually requires a substantial time and financial commitment to marketing, and a long enough runway (more than 18 months) for it to pay off.

This is even more true with apps in the app store, because there is a substantial behavioral hurdle to get users to download the app. It’s possible to do (we’ve achieved 6x conversion rates compared with the industry norm for growth clients willing to dedicate the time and resources) but it doesn’t come easily. If you’re picturing a leisurely stroll to wild success, this probably isn’t the best path.

Efficiency apps on the other hand, though potentially less compelling at first glance, yield more consistent, measurable returns. If you’re considering an app that allows you to serve your existing business better and deepen those relationships, the data backs up your hunch that this is likely a good investment.

How can we apply lessons from prior hype cycles to AI development?

While we’re still early in the life cycle of AI, we can learn from the way mobile app investment has evolved. It’s likely that efficiency plays will continue to be safer bets, though volume may deter some very small businesses from investing due to the ‘size of the pie’ problem discussed earlier. However, this doesn’t have to be a deterrent.

AI investments are, on the whole, more affordable than creating new mobile apps. We’ve quoted many AI enhancements to existing applications in the 15-30K range, and many new AI-integrated web applications in the 60-85K range. You’d be hard-pressed to develop a credible mobile app for even double that. So, the more favorable cost profile of web development as compared with mobile app development comes into play for many of these AI investments, especially in the internal and B2B spaces where web is the preferred platform. While the AI giants are spending billions, individual companies implementing AI can do so fairly affordably. The lower cost means a lower barrier to entry, and a lower required return to make the whole thing pay off. That means a piece of even a small efficiency pie may justify an investment.

On the other hand, AI investments carry more inherent unknowns in the output itself. Unlike traditional programming, AI integrations all carry some degree of inconsistency. These ‘hallucinations’ are an expected part of the process and smart product owners take them into account. AI can be especially effective in efficiency investments. The nature of an efficiency investment lends itself to putting in place the guardrails today’s AI needs, while planning for an even more transformative future.

Users are also getting savvier about AI every week. This means as comfort levels with AI grow, I expect to see people react less negatively to hallucinations and treat them more as an expected part of the process. That’s already effective for internal uses of AI (especially in the efficiency space) but I expect to see this also influence growth investments in AI. Perfection doesn’t need to be the standard forever, as long as there are appropriate fallback mechanisms to protect the end user.

Is it time to invest in a pickaxe?

With the hype giving way to clearer thinking, companies of all sizes have an opportunity to breathe and evaluate the business case for tech investments based on real numbers rather than FOMO. If you’re an entrepreneurially-minded leader, it’s okay that your natural inclination is likely to be to swing for the fences with growth investments. To improve your odds, make sure you adequately understand what it will take to break into a new market, and ensure you have the runway to do it.

If not, it’s okay to hit pause. You’re not missing out. And above all, make sure you have the appetite for the risk involved.

For those with a more enterprise attitude, know that the efficiency investments, while not always as compelling in a press release, have a proven track record of nearly double the success rate. Those are a strong bet when money is tight, or organizational appetite for risk is lower.

Notes

I expect these numbers to change a little before final release. We still have some data missing from the dataset that needs to be tracked down, and some decisions to be made about how we’re pulling stats (Straight count of properties? Some properties contain multiple projects. Count of projects? Releases? Those sorts of questions). Nonetheless, I expect them to remain directionally accurate.